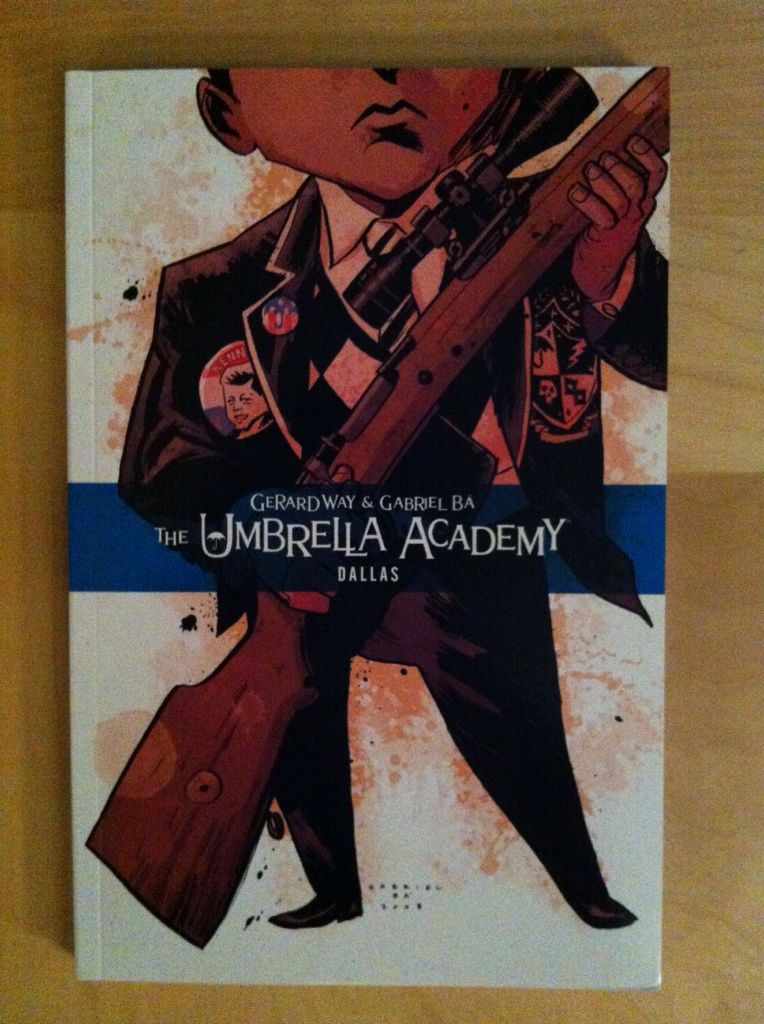

A 250 word (or less) review of the second The Umbrella

Academy collection

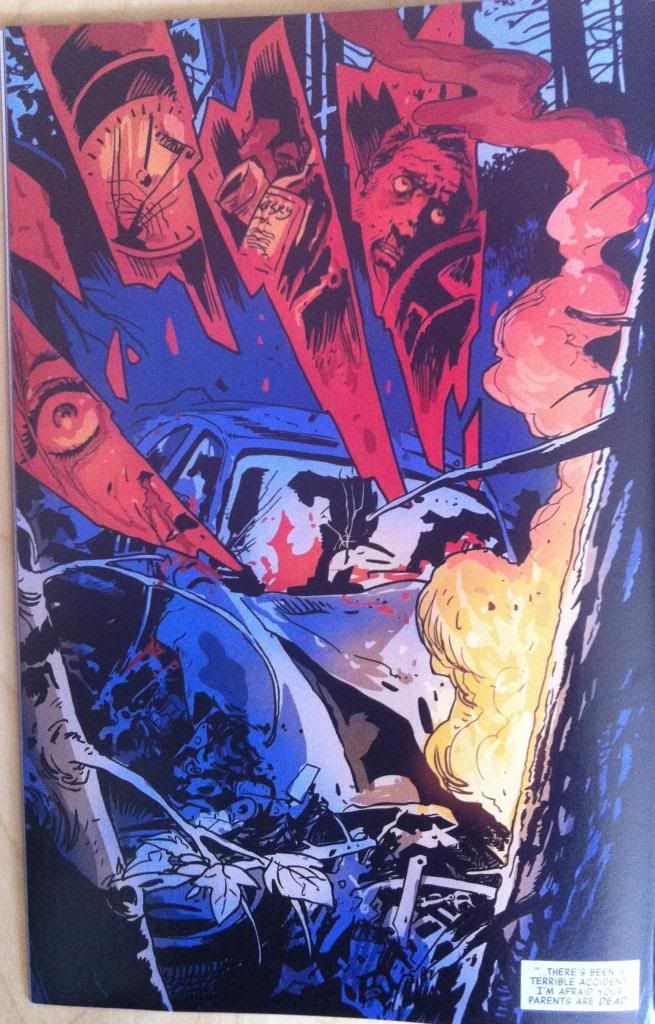

Now this is more like it! I liked the first collection of The

Umbrella Academy, Apocalypse Suite. I thought it had some neat ideas, amazing

art, and solid storytelling, but felt that it was maybe too conventional? Too

adverse to risk? Like, that the premise had a certain amount of untapped potential,

which, if it could be wedded to Ba’s astounding art, could make The Umbrella

Academy a truly great comic. I am happy to report that Dallas lives up to the full

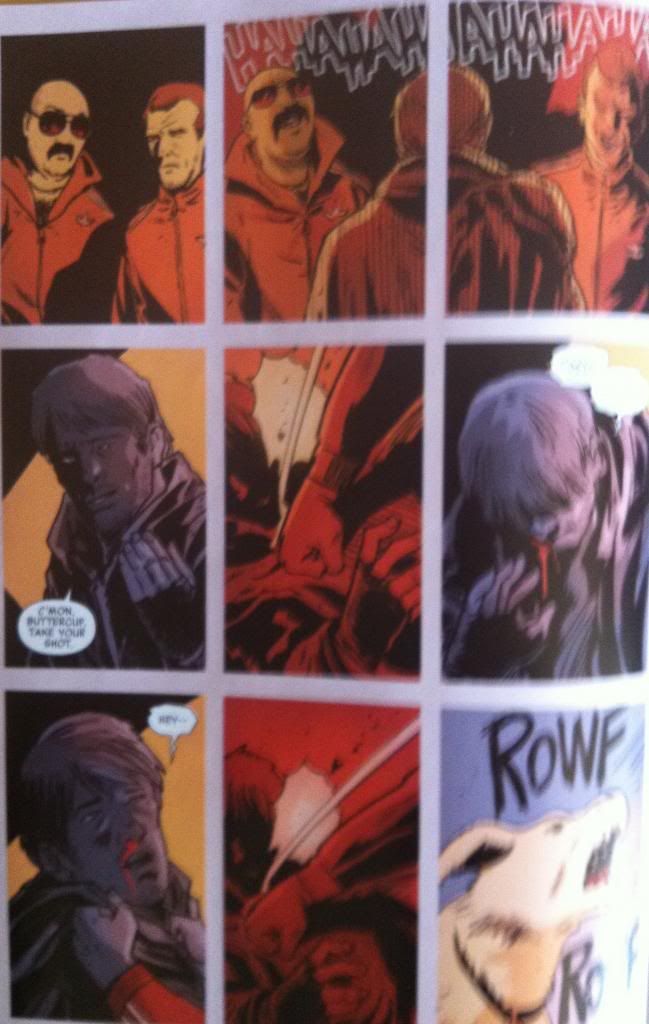

The Umbrella Academy potential. Dallas picks up where Apocalypse Suite leaves

off, with the super-powered orphans of the academy traumatized, maimed, and

scattered from the fallout of the previous chapter. Against this stark tableau

the secret future/history of Number 5 is revealed as well as the horrific

mission he and his family must undertake to save the future. It is, more than anything, a

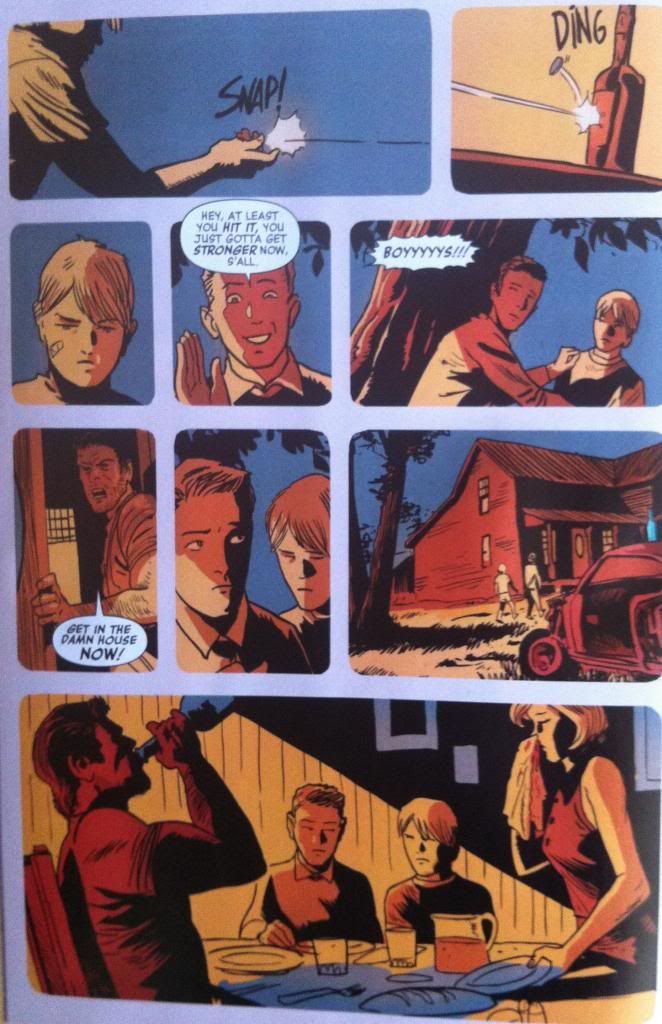

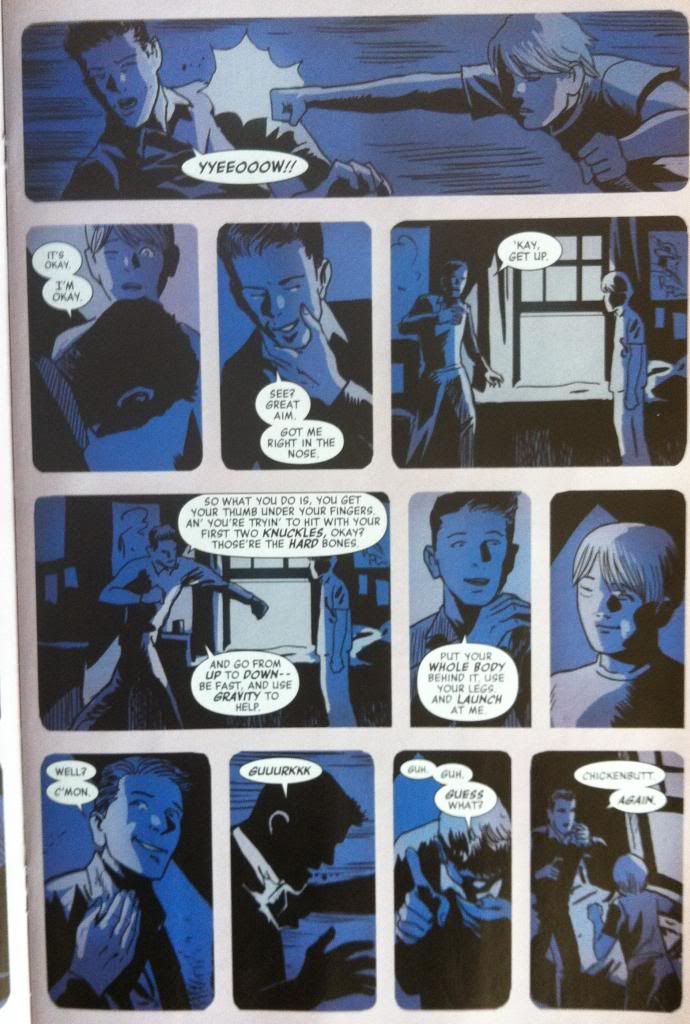

confounding and brave comic. Where Apocalypse suite is kind of an avant garde

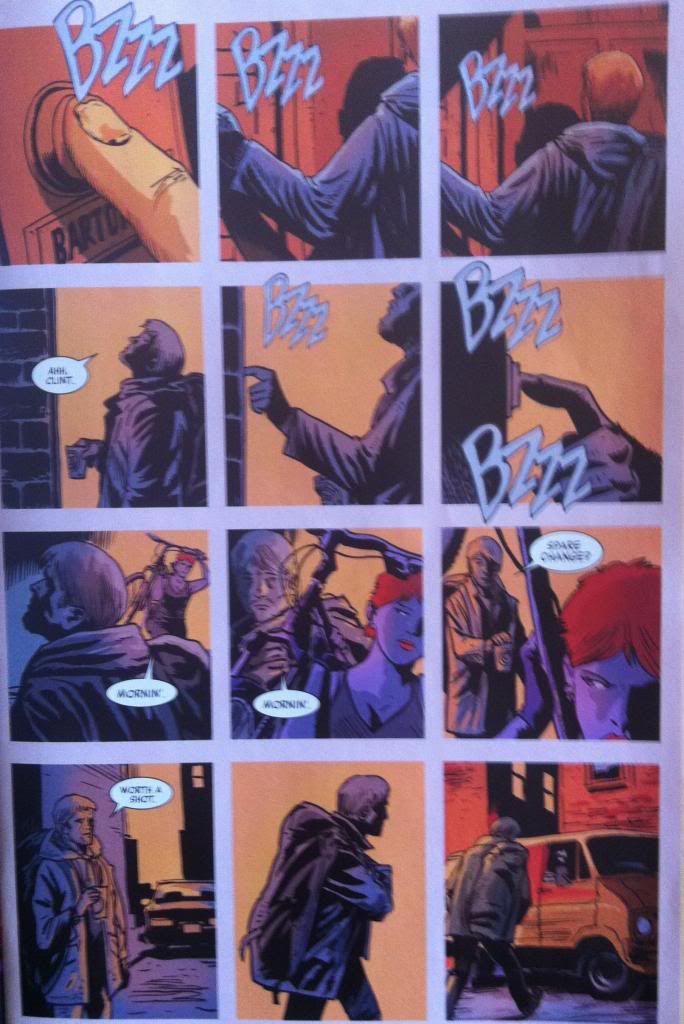

take on the Superhero formula, Dallas is just balls out crazy originality. It’s almost as if, with the basic

foundations of The Umbrella Academy world established, Way and Ba are free to

capitalize on their creativity. Every single page crackles with this manic

energy and nearly every scene goes in an unexpected, yet satisfying

direction. The entire comic is expansive and interesting and just utterly

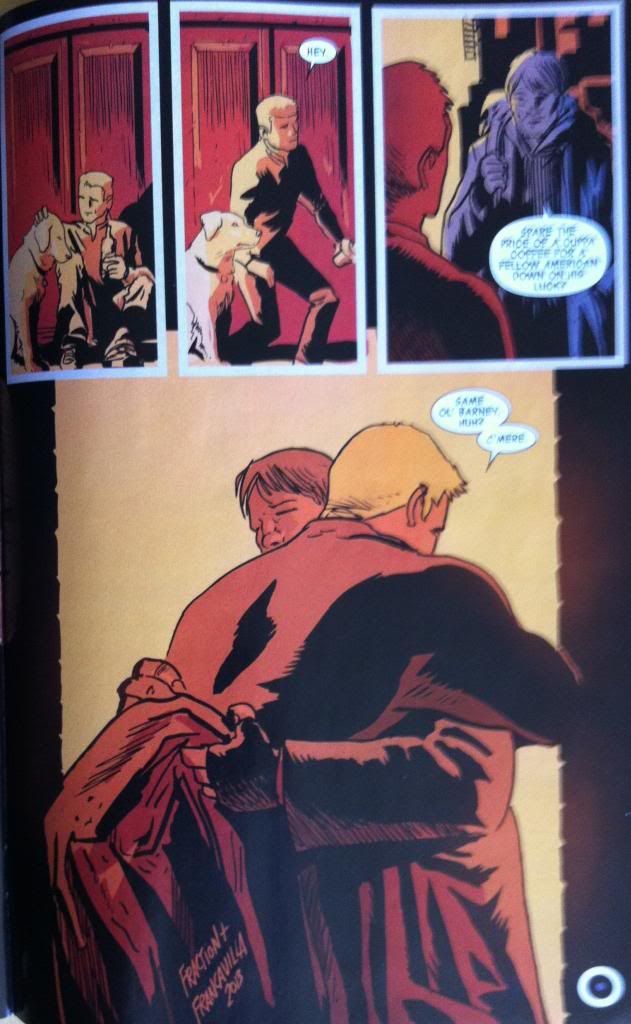

weird. Dallas is absolutely its own thing and it’s great. The Umbrella Academy:

Dallas is the complete, realized Umbrella Academy package. It’s well worth reading.