By Kelly Sue DeConnick, Filipe Andrade, Jordie Bellaire; Marvel Comics

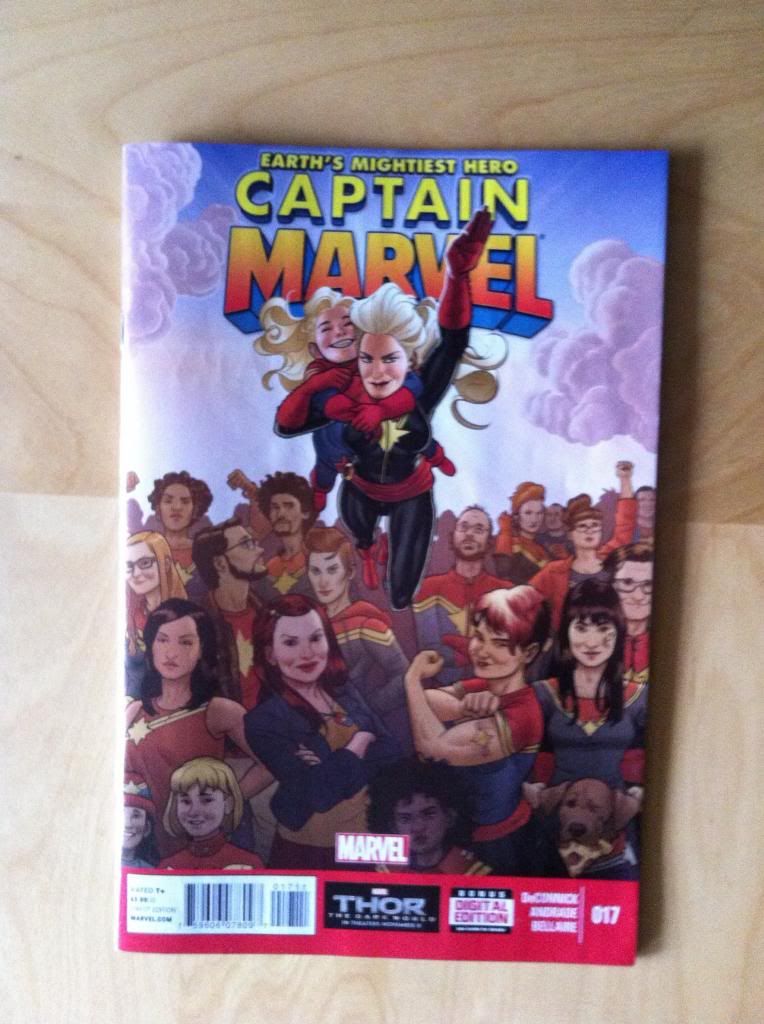

Captain Marvel #17 is one of those comics I can't stop thinking about. It features gorgeous artwork by Filipe Andrade and Jordie Bellaire and hits the rarified air of a comic worth purchasing for the art alone. The story is full of charm, humour, and jaw-droppingly perfect moments with the rich character work and relationships that are the foundation of the series. It's a really fun, really emotionally satisfying issue of comics. But the reason that I can't stop thinking about CM#17 is that it's this amazing meditation on the relationship between superheroes comics and their fans. And this is completely worth trying to unpack.

There will be *SPOILERS* for Captain Marvel #17 in this post.

I'm a fan of Captain Marvel, I think it's been a really great comic by A-list creators which has pretty consistently told really great stories. When not dealing with crossovers, team Captain Marvel have turned in some of the best issues of comics I've read. And I'm clearly not alone in this: Captain Marvel has a fiercely loyal fanbase, The Carol Corps. A group of readers who don't just read Captain Marvel but engage with it, create Captain Marvel fanart, cosplay as the Captain, knit Captain Marvel woolies, and permanently scar their body with tattoos from the series. A group of people who gather in online spaces, including the really terrific one curated by series writer Kelly Sue DeConnick, to share and celebrate Captain Marvel and the series creators.

Captain Marvel #17 explicitly deals with this aspect of fandom. The premise of the issue is that the folks of New York City, in return for Captain Marvel's efforts to save the city from Yon-Rogg (Events from The Enemy Within Corssover), are throwing a rally of gratitude for Carol Danvers. This is literally a comic where the fans of Captain Marvel gather to celebrate their hero and show their appreciation of events which had taken place in a comic book. These are in continuity characters doing what we as fans do online after every issue.

Inherent in the nature of superhero comics, particularly Captain Marvel, is an element of aspiration. These are stories about being better than mortal, about fighting for an ideal, and about helping people. As a result superheroic comics can be very inspirational to fans. (Or maybe they just attract people for whom inspirational stories resonate...) And Captain Marvel has managed to be a pretty inspirational comic to a lot of people. With themes of heroism, particularly heroic women and relationships, Captain Marvel has become a kind of rallying flag for a group of women geeks who are often ignored or treated poorly by comics. Moreover, The Carol Corps, inspired by Captain Marvel, the creators, and each other have leveraged their fandom into a force for good by donating to charities and disaster relief funds. It's pretty damn cool to see.

Captain Marvel #17 acknowledges the aspirational nature of the hero fan relationship as well. In this case the comic uses the relationship between Carol and Kit, her young fan and neighbour, as the lens to frame this. The ongoing comic and CM#17 explicitly show that Kit sees Captain Marvel as a hero and that she clearly looks up to her. Captain Marvel #17 also has a scene where Kit stands up to a bully picking on a cosplaying friend in a way that feels very much inspired by the heroism of Carol. It's a pretty great scene that I think really strikes at the ideal of fanspiration.

The reality of comics is that they are a business: people ultimately have to buy comics for comics to be made. Creators have to be remunerated for their labour, printing and publishing costs have to be covered, and, especially for Marvel and DC comics, profits have to be realized. A book like Captain Marvel has a mandate to sell at a certain level to justify its existence. Failure to find an adequate audience ensures the books cancellation. In an environment where every new series and number one comes with a burst in sales, Captain Marvel exists during a time when there may even be an incentive to cancel under-performing, or perceived to be under-performing, titles. What this means is that for Captain Marvel to have her amazing adventures, for the creators to tell her stories, fans have to buy her comic. Captain Marvel needs her fans to be our hero.

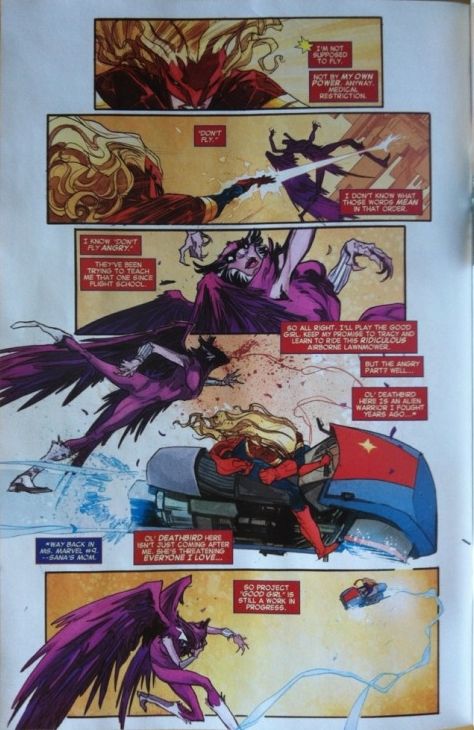

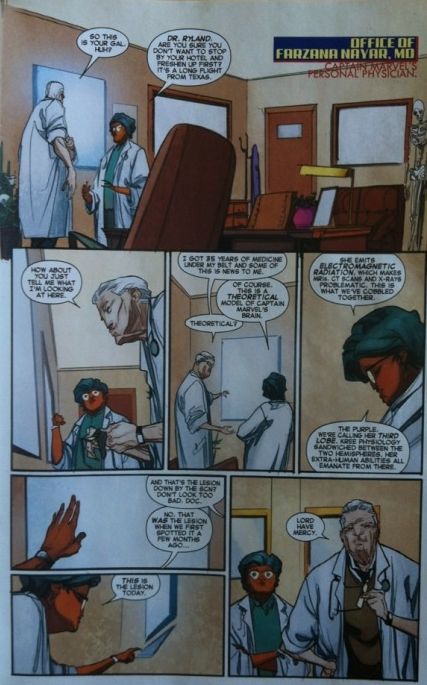

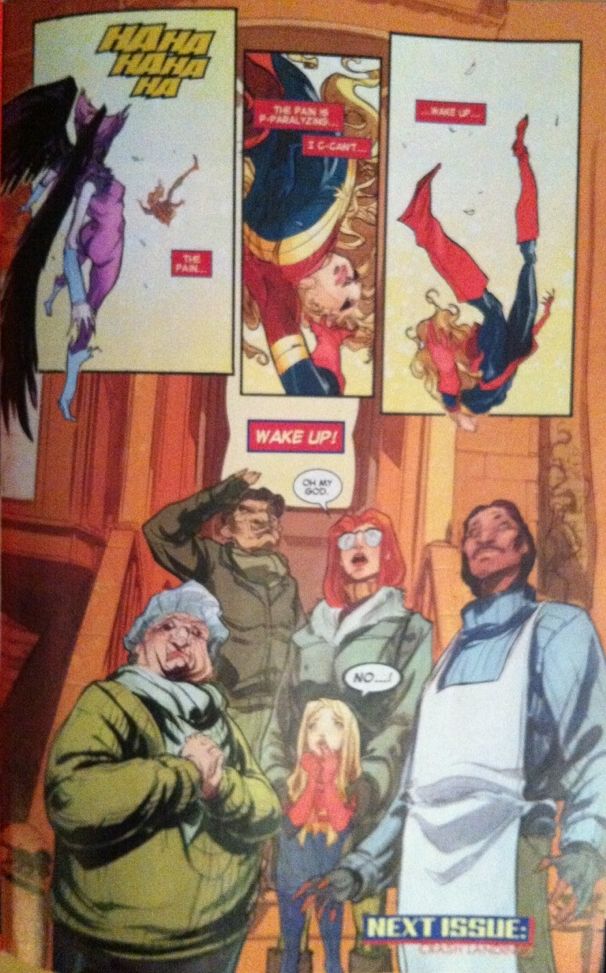

Captain Marvel #17 tackles this aspect of comics as well. The conflict of Captain Marvel #17 is that a young business professional, with dubious morals and Ayn Randian Objectivist worldview, is bumped from a magazine for a Captain Marvel profile and wants revenge. Since this is comic books she decides the reasonable response is to send a flock of missile drones to attack Captain Marvel appreciation day. Explosions happen, Carol is vulnerable, and her fans have a "I am Sparta-err-Captain Marvel" moment which confuses the drones targeting software. This gives Carol the moment she needs to collect herself and superhero the crap out of the missile drones. But, from a more meta-relevant perspective, Captain Marvel is literally being saved from the personification of Capitalist forces by her fans. Which, I think, is a pretty deliberate shout out to the fans of Captain Marvel who've helped keep the series alive.

I frequently get the impression that the creators of Captain Marvel, particularly Kelly Sue DeConnick, enjoy the interactions they have with The Carol Corps and non-affiliated fans. It seems, as an outside observer, that team Captain Marvel is touched by the fact that a strong enough fanbase came out and bought Captain Marvel that the series ran 17 issues and is being relaunched and also getting a spinoff series. (A feat which apparently resulted in a lost bet.) It also seems, as an outside observer, that the creative people who make Captain Marvel are amazed by all of the fan generated creative projects, the charitable generosity of the Carol Corps, and pleasant demeanour and inclusiveness of much of the Captain Marvel fanbase. (Which hopefully balances out the soul destroying nonsense of the human garbage scows that Team Marvel doubtlessly also have to deal with.) Collectively, it seems to me that the creative team behind Captain Marvel is somewhat inspired by their readers.

Captain Marvel #17, I think, rather explicitly states this point. In one of the closing scenes of the issue, Captain Marvel and Kit are hanging out in Carol's new home, the gallery of the Statue of Liberty (and how many kinds of awesome is that!?), to have a "Captain Marvel Lesson". Captain Marvel, suffering as she does from memory loss (Enemy Within), confesses to Kit that she is unsure how to teach her how to be Captain Marvel. It's at this point that Kit reveals that her plan was, all along, to teach Carol how to be Captain Marvel using a comic book she made. Or, to meta this up, Kit, the ultimate Captain Marvel fan, is going to teach Carol what it means be Captain Marvel using the lens of being a fan. Which I feel is a pretty obvious "thank you" from Team Captain Marvel, as well as a revelation that the Carol Corps has helped shape what Captain Marvel means to its creators and maybe even changed how they think about heroism a bit.

So, to try to integrate this whole thing, Captain Marvel #17 seems to suggest that this construction of Captain Marvel (character/book/community) has arisen from a kind of collaboration between creators, the character, and fans. This comic, I think, shows that while fans come to the comic for the character (and creators) and can draw on the book for inspiration, ultimately the creators rely on their fans and are in turn inspired by them. And the result of all of this is Captain Marvel and the Carol Corps and all of the fictional and real world goodness that's come out of this funny book. And that is pretty damn special and is why I can't stop thinking about Captain Marvel #17.

You really ought to be reading Captain Marvel and if you aren't, you should try out the nuCaptain Marvel book when it launches. It's gonna be a REAL comics party.

Previously

Marvelling at Captain Marvel 15-16: On tie ins

Marvelling At Captain Marvel #13-14: On The Enemy Within

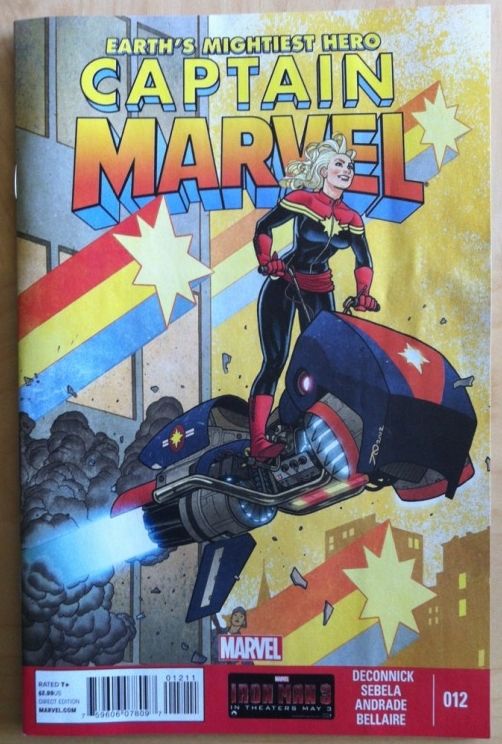

Marvelling At Captain Marvel #12: Demarcating reality and fantasy

Marvelling At Captain Marvel #10: A dramatic contract

Marvelling At Captain Marvel #9: How your brain tells time

Marvelling At Captain Marvel #7: Saving a reporter in distress... AND ITS A MAN!

Marvelling At Captain Marvel #1: An alternate reading order that I liked more