by Jeff Lemire, Greg Smallwood, Jordie Bellaire, and Cory Petit; Marvel Comics

Moon Knight #1 is the kind of comic I usually steer clear of. It's a relaunch of a series that has just been relaunched several times. I fairly recently read an iteration of the series that I *really* enjoyed as a cohesive, complete experience. I don't really have strong feelings about Moon Knight as a character, and since reading a little Cerebus I'm having some trouble taking him seriously ("Unorthodox Economic Vengeance!"). And yet... Jordie Bellaire only seems to work on good comics, Jeff Lemire has created several comics I enjoy, and Greg Smallwood's artwork is immediately, obvious good. So it's really on the strength of the creative team that I even tried this comic. And I am pretty glad that I did.

Moon Knight #1 is also the kind of comic I love to write about: it is a very accomplished comic that uses a number of stylistic elements to convey narrative information and create an immersive reading experience. Which I'll try and unpack below.

There will of course be *SPOILERS*.

One of the choices I really like about Moon Knight #1 is the use of very wide white gutter spaces. This choice gives the entire comic a soft, almost hazy feeling. This effect is apparent throughout the issue, but is particularly obvious in certain pages which actively use the white space to show Spectre slipping in and out of consciousness, whiting out in what feels like a slow and muzzy way. Overall, I suggest the passive and active use of white margins works to create a sense of floating, semi-conciousness that really adds to the ambiguity of the comic and sense that the narratoring perspective may be unreliable. It's great stuff.

Another of the stylistic choices in Moon Knight #1 that I find so effective is the dual colouring styles used in the issue. The comic opens on a pair of pages of Marc Spectre exploring an Ancient Egyptian temple as part of a hallucination/vision. This sequence features a grainy, sketchy colour palette that uses 'painted' highlights and specks of pigment to create a decidedly artificed world. By which I mean, the stylistic choices of this opening sequence manages to look like something created by an artist (a fictional environment) but also extremely granular and high resolution (a hyper-realistic environment). The more mundane elements of the comic which tell the story of Marc Spectre committed to some sort of mental hospital feature flat colours and a much more conventional comics look. This creates an immediate codified demarcation between the fantastical world of the comic and the mundane world.

Part of what makes this colouring choice so powerful in the comic is how it works to collide the supernatural/insane elements of the comic with the mundane. When Spectre becomes Moon Knight or hears the voice of his god Kohnshu elements of the scratchy, granular colouring creep into the comic, creating an emotional contrast between these elements. This also creates a palpable sense of dread/power in the supernatural elements: they feature distinct colouring so *something* must be happening, maybe Spectre isn't insane...

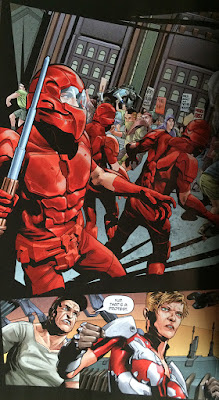

And then there are the pages where the divisions break down and the flat colouring of the mundane world and the gritty, sketchy aesthetic of the supernatural collide. Where Moon Knight is free to attack the nurse/jackals that have been imprisoning and seemingly abusing him throughout the comic. This is depicted wonderfully in a flurry of small, circular panels that chaotically capture individual moments of violence. It's a page out-of-control and unhinged, and manages to capture a maniac fury in a clear and visually interesting way. Collectively, it's a great choice that I think manages to establish this incarnation of Moon Knight as dangerous and which implies that there is potentially an element of supernatural power about the possibly insane man.

I think this double-page spread is my favourite use of the supernatural/mundane colouring. The page depicts New York apparently mixed up with some sort of Ancient Egyptian-inspired hellscape. While I can spot elements of paint splatter and sketchy colours, these elements are subdued compared to panels and sequences that are more clearly entrenched in either Spectre's mind or the possibly hallucinated. Instead this page features mostly the more flat colouring of the mundane elements of the comic, despite the impossible thing being depicted. The white margins also fall away for the first time in the comic, making the page feel bigger, sharper, and more real. This creates this wonderful moment of ambiguity: is this all a hallucination of Spetre's? Could this really be happening? The colouring, which has been used to codify this, is unclear. And so by establishing, utilizing, and then subverting the colour conventions of the comic, Moon Knight #1 manages to call into question what in the comic is even really happening. Which is great.

I read Moon Knight #1 because of the creative team, but will read #2 on the strength of the execution of the first issue.

Previously: